Researchers have identified a new mechanism that not only retards the aging process but also increases the longevity of the immune system.

The normal aging of immune cells is one of the nine 'hallmarks of aging,' but an international team led by UCL researchers has uncovered a new mechanism that slows and, in some cases, prevents this process.

Nature Cell Biology reported an "unexpected" finding in cells in a lab and confirmed it in mice. The investigators think that by employing this strategy, the immune system can function more optimally and live longer in its fight against diseases like cancer and dementia.

The study's senior author and an honorary professor at UCL's Department of Medicine, Dr. Alessio Lanna, stressed that the immune system is always on guard. They need a long half-life in the body to have any effect. Though this lifetime security is provided, how this is accomplished is most mysterious.

This research aimed to learn how T cells in the immune system are given a longer lifespan at the outset of the immune response to an antigen, a foreign substance detected by the immune-surveillance mechanisms of the body's defense.

In what ways does the immune system decline with age?

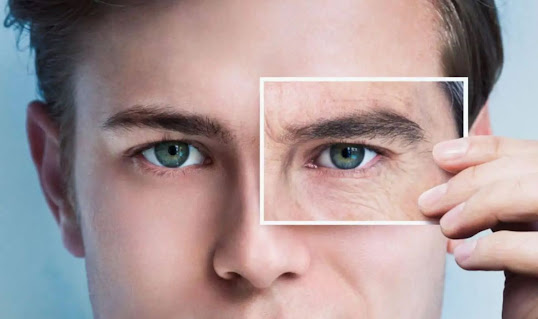

A cap at the end of each chromosome in a cell called a telomere is made up of a specific DNA sequence replicated hundreds of times. The sequence serves as a biological clock that controls the maximum number of cell replications (also known as cell divisions) a cell can undergo. It also protects the coding regions of the chromosomes.

Telomeres shorten with each cell division in T cells (a type of white blood or immune cell) and most other cells (telomere attrition). The cell enters senescence when its telomeres become too short, at which point it either ceases dividing and is disposed of by the immune system or persists in an altered, dysfunctional state until it dies.

Damaged immune systems lead to persistent infections, cancer, and early death. Attrition of telomeres has been called a "hallmark of ageing."

Conclusions from the Research

This research involved stimulating an immune response against bacteria in vitro using T cells (foreign infection). As a complete surprise, scientists found that two distinct types of white blood cells could undergo a telomere transfer reaction via a molecule called an 'extracellular vesicle' (tiny particles that facilitate intercellular communication). The antigen-presenting cell (APC), which could be B cells, dendritic cells, or macrophages, "donated" a telomere to the T lymphocyte. Following telomere transfer, the recipient T cell acquired the properties of a memory cell and a stem cell, making it capable of providing lifelong immunity against lethal infection.

The telomere transfer process was responsible for stretching some telomeres by a factor of 30 greater than telomerase. Among the several DNA-making enzymes, telomerase is the only one that helps maintain healthy telomeres in stem cells, immune system cells, fetal tissue, reproductive cells, and sperm. Nevertheless, telomere attrition occurs because this process is absent in other types of cells. However, continuing immune responses promote progressive telomerase inactivation, leading to telomere shortening and replicative senescence when cells stop replicating. This occurs even in immune cells, where the enzyme is naturally active.

According to Professor Lanna, "the telomere transfer response" between immune cells adds to the Nobel-prize-winning discovery of telomerase. Cells can transfer telomeres to adjust chromosome length before initiating telomerase action. The telomeres transfer can potentially retard or even reverse the aging process.

Utilizing the brand-new system

As a follow-up to their discovery of the unique "anti-aging" mechanism, the same research team showed that telomere extracellular vesicles could be extracted from blood and, when paired with T cells, exhibit anti-aging effects in the immune systems of both mice and humans.

Purified extracellular vesicle preparations can be given alone or with a vaccine to produce long-lasting immune responses that, in theory, can prevent repeated immunizations.

The 'telomere donor' transfer process in cells can be actively stimulated. They say this highlights the promise of new prophylactic (preventative) therapy for immunological senescence and aging, albeit much more study is needed.

Researchers have been looking into telomeres for over 40 years. For a long time, scientists assumed that telomere elongation and maintenance in cells were solely the work of a single enzyme called telomerase.

Professor Lanna says, "Our results explain how a new mechanism that does not require telomerase to extend telomeres and work when telomerase is still inactive in the cell."